Quick facts

(Figures for 2025; Sources: BWO, BWO, Fraunhofer ISE)

Number of turbines installed: 1,680

Total capacity installed: 9.7 GW

Expansion Target: 30 GW (2030)

Share in net power production: 6.2%

Output: 26.1 TWh

Employees: ≈30,000

Overview

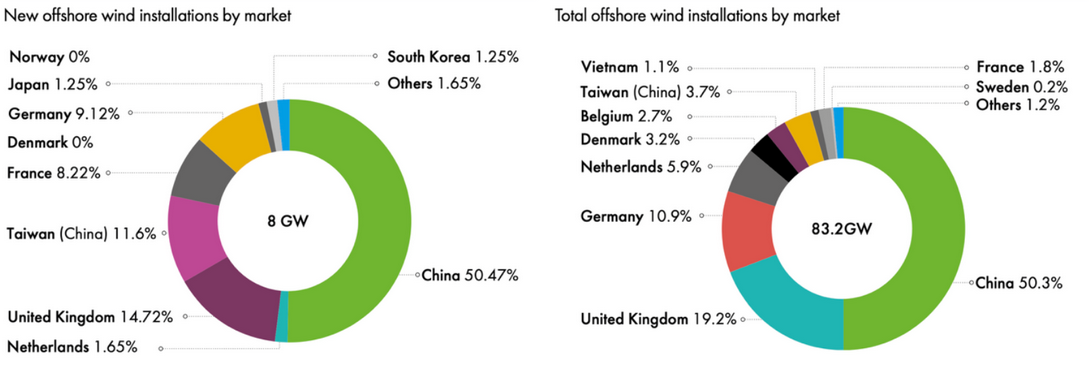

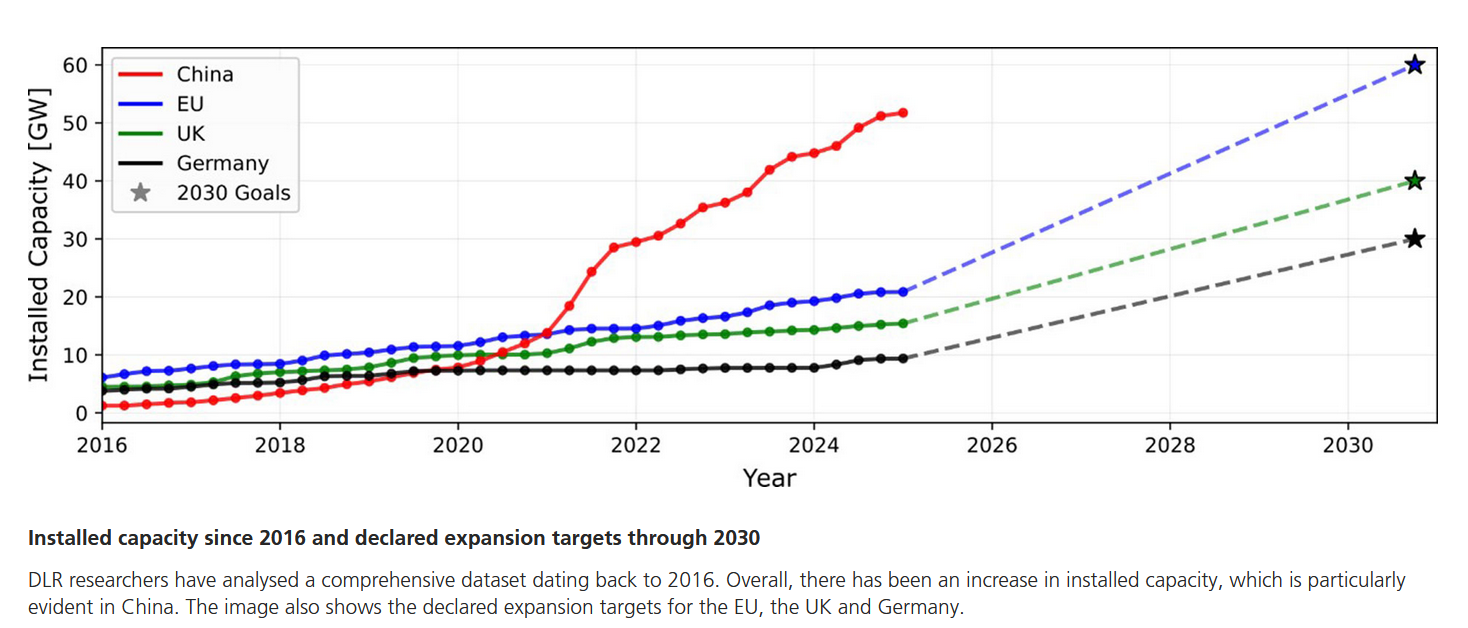

Germany was among the first countries in the world to launch offshore wind power generation at a large scale. After opening its first wind farm in 2010, the country’s installed capacity in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea grew quickly, making it an early leader in a technology widely seen as one of the most reliable and promising renewable energy sources. Consecutive failures to uphold strong expansion rates, however, caused the country to slide in global buildout rankings: While Germany's offshore turbine capacity accounted for 40 percent of the global share in 2017, its share fell to less than 11 percent in 2025. As of 2026, however, it still boasted the third-largest total capacity after China and the UK.

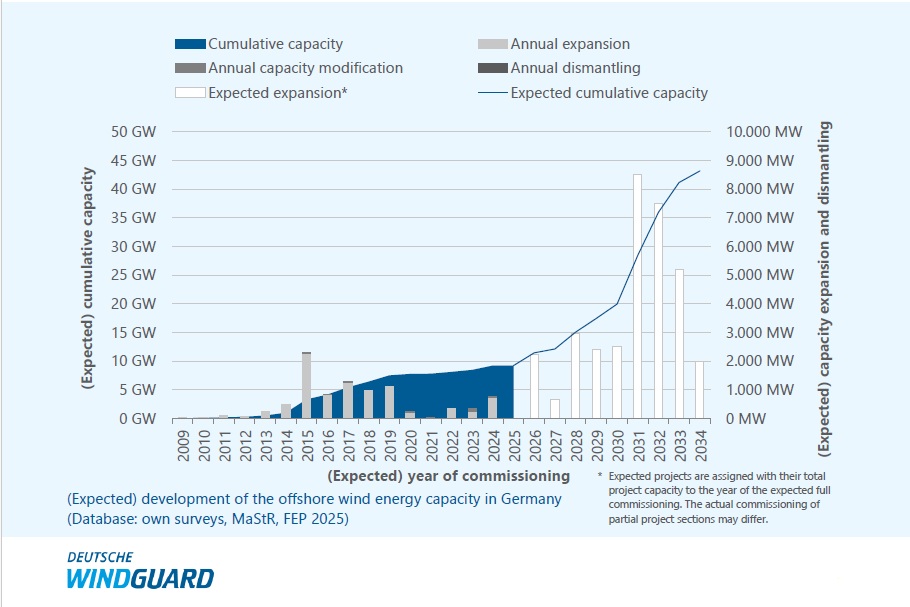

At the beginning of 2026, a total of 1,680 turbines with a combined capacity of 9.7 gigawatts (GW) were in operation in Germany’s territorial waters. This is still far from the government’s 2030 capacity target of 30 GW, which would require a tripling of installed capacity within five years. In 2025, only 41 turbines with a combined capacity of 0.5 gigawatts (GW) were connected to the grid, continuing an extended period of slow progress. Industry representatives therefore say the target will likely be missed and estimate total capacity to reach around 20 GW by the end of the decade.

Offshore wind’s contribution to Germany’s power production mix reached 6.2 percent in 2025 (up from merely 0.1 percent in 2014). This was despite relatively weak wind conditions that cut output by nearly one third at the beginning of the year. According to offshore industry lobby groups, the technology could ultimately provide up to one quarter of the country’s electricity demand.

Germany aims to bring the share of renewables in the power mix to 80 percent by the end of the decade, from just over 57 percent in 2025, and to achieve a completely greenhouse gas-neutral electricity system by 2045. While the government under chancellor Friedrich Merz has considered adapting offshore wind capacity targets to reflect lower-than-anticipated growth in electricity demand, the fleet is still scheduled to grow to 40 GW by 2035 and 70 GW by 2045.

Investors wary despite huge cost reductions

Offshore wind turbines have immensely grown in size and capacity since they entered the market in the early 2000s, to an average capacity of 12 megawatts and an average rotor length of 211 metres for new installations in 2025. Offshore turbines are also larger, more productive and more reliable than their onshore counterparts.

The growth in size and average output has been key to the fall in power generation costs in recent years. Harvesting the power of strong, continuous winds at sea, they deliver electricity to the grid almost all year round and produce nearly twice as much electricity as land-based turbines, according to wind power consultancy Deutsche Windguard. Offshore power generation has proven so reliable that grid operators in 2022 started using the turbines to stabilise the country's electricity system in case of fluctuations, a role that until then had been reserved for fossil power plants.

Thanks to fast progress in cost reductions, the first projects no longer requiring state support were announced by investors in 2017, further solidifying offshore wind’s promise to become a cornerstone of the energy transition. Investor confidence in the installations’ profitability surged and quickly resulted in ranking bidders by their willingness to pay an ‘entry-fee’ for building wind farms at sea, rather than by who required the least support.

However, according to industry group BWO, the investors’ confidence in the tenders concealed underlying difficulties in getting projects to work according to schedule and with optimal output, as limited capacities for construction, grid connections, and designated areas at sea complicated implementation. In 2025, the country then saw its first auction in which no bids were submitted at all, exposing challenges in the current approach.

Industry representatives and government members from Germany’s coastal states therefore called for postponing the auction round planned for early 2026 to avoid another zero-bid outcome. The federal government ultimately agreed and rescheduled the round for 2027. Industry representatives said a new auction design should exclude negative bids and take the European market framework more into account, including through schemes such as contracts for difference (CfDs) or power purchase agreements (PPAs).

A highly anticipated reform of Germany’s Renewable Energy Act (EEG) that is due in 2026 is expected to provide more clarity regarding future funding models and the broader expansion path. Industry representatives worry that the government might scale back renewable energy support in response to a monitoring report on the energy transition published in 2025. With electricity demand trailing initial estimates in the medium term, investor confidence is heavily influenced by the government’s willingness to bolster the offshore wind industry at this stage despite its significant cost cuts.

Growing turbine density a concern for business and environment

Offshore wind power installations generally face fewer spatial constraints than onshore projects, thanks to higher average wind yields at sea and the absence of direct nearby residents or infrastructure that turbines could interfere with. However, construction space is also limited offshore and the challenge is particularly acute in Germany, a country with a relatively large land mass and population but a comparatively small share of maritime zones. The Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) defines specific areas for wind energy, sets tendering conditions, oversees commissioning and determines grid connection requirements.

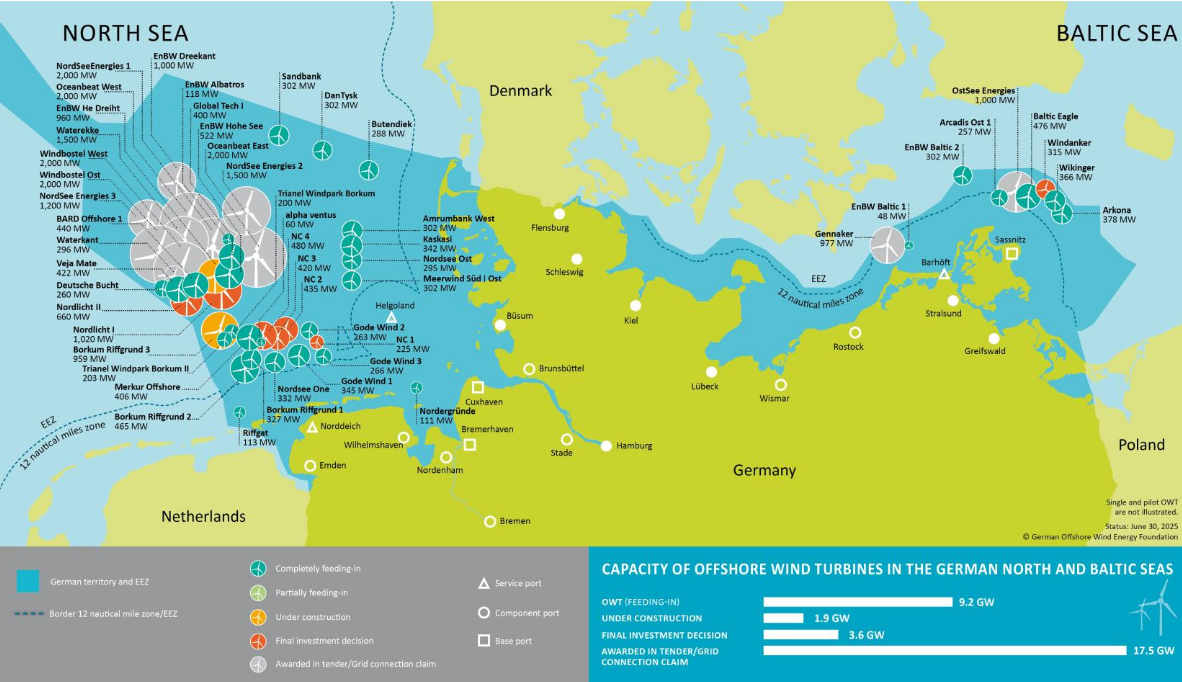

The vast majority of Germany's offshore turbines are located in the North Sea, where output per turbine on average is much higher than in the Baltic Sea. Nearly 8 GW in about 1,370 turbines were installed off Germany’s western coast at the end of 2025, compared to just under 2 GW in a little over 300 turbines in the Baltic Sea to the east. Future expansion is therefore set to concentrate primarily in the North Sea, a region where other projects from the UK, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany together have created one of the world’s largest offshore wind clusters.

However, electricity output decreases considerably if windfarms are located too close to one another due to wake effects, while competition for available grid capacity to transmit power onshore intensifies. At the same time, the environmental impact on marine ecosystems increases with turbine density. This is a particular concern for the protected Wadden Sea area in the North Sea, an important bird migration site, and for endangered species, such as harbour porpoise whales.

To unlock additional sites, Germany has begun surveying locations further offshore to assess the viability of more remote wind farms. Distributing turbines more evenly across the country’s territorial waters could improve efficiency, but closer coordination and cooperation with Germany’s coastal neighbours may offer even greater gains. An analysis by research institute Fraunhofer IWES found that partially shifting Germany’s planned expansion to 70 GW by 2045 into the territorial waters of Denmark and Sweden could increase output, lower costs and improve supply stability by reducing the risk of regionally weak wind conditions.

International cooperation offers new perspectives

The potential of offshore wind power as a cornerstone of a decarbonised energy system has prompted many countries to adopt ambitious expansion targets, with northwestern Europe being a focus region. At a summit in Hamburg in early 2026, North Sea states pledged to install up to 300 GW of offshore wind capacity and turn the sea into “the world’s largest energy hub” (up from a combined capacity of 37 GW at the end of 2025).

The initiative includes plans to mobilise up to one trillion euros between 2031 and 2040 to install up to 15 GW per year. Participating countries aim to rapidly expand interconnectors so that several states can draw electricity produced in the same wind farms, and to develop joint approaches to protecting critical offshore infrastructure. At the summit, Germany and Denmark also announced the first offshore wind project jointly financed by two countries: the 3 GW Bornholm Energy Island, which is designed to turn the Danish Baltic Sea island into a hub supplying power for up to three million households in both countries.

Cooperation with the participating states predates the first “North Sea Summit,” which was launched in 2022 as a platform to strengthen European energy sovereignty following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and when Germany agreed with Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark to expand offshore wind power generation capacity tenfold to at least 150 GW by 2050.

Together with Norway, Germany built the NordLink cable with a capacity of 1.4 GW, which entered into operation in 2021 and allows surplus offshore wind power from Germany to be balanced with Norwegian hydropower, increasing electricity supply security and price stability in both countries. Offshore wind also is a focus area for in linking German and French energy transition plans, with both countries seeking to improve cost competitiveness and support the development of hydrogen production at sea.

Cooperation with the UK has intensified since Britain’s exit from the EU, bucking a trend towards looser ties in other policy areas and culminating in a pioneering multi-purpose interconnector project in early 2026. Germany likewise sought closer cooperation on joint offshore wind with neighbours in the Baltic Sea, a region where its insistence on the now defunct gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 linking it with Russia strained diplomatic relations on energy policy.

Industry hopes for stable employment, wary of Chinese advances

The offshore wind industry has become an important employer in Germany’s coastal regions and also for industry suppliers elsewhere in the country. However, job prospects largely depend on political decisions, particularly on expansion targets that provide investors with long-term planning security. According to industry association BWO, employment in the highly specialised sector reached about 30,000 in 2025. At the same time, a shortage of skilled workers able to install, operate and maintain renewable power infrastructure has emerged as a broader challenge for Germany’s energy transition.

Germany’s largest turbine maker, Siemens Gamesa, topped the world’s offshore turbine manufacturer ranking by Bloomberg NEF in 2025, while Chinese companies dominated the onshore segment. Offshore wind has created jobs for bearing, gearing and generator manufacturers across the country, but coastal regions benefit most directly. Shipyards and specialised service providers supplying maintenance crews and operating personnel are also profiting from the expansion. However, observers have warned that insufficient port capacities and a shortage of construction vessels could become bottlenecks that slow the buildout’s pace in the next years.

Ports on the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, including Bremerhaven, Cuxhaven and Rostock, are therefore upgrading infrastructure to handle increasingly large turbine components, foundations and related equipment. Heligoland, a small German North Sea island about 65 kilometres offshore, aims to position itself as a hub for offshore wind servicing and for green hydrogen production, using wind energy to produce storable fossil-free fuels on site.

A more strategic concern for Germany’s offshore wind industry is growing competition from Chinese manufacturers. Although a controversial decision to deploy Chinese turbines in a German offshore project was reversed in 2025, the sector remains wary of lower-cost Chinese competitors, particularly after Europe’s domestic solar power industry largely lost out to Asian competitors. As of 2025, the Asian economic heavyweight operated just over half (51%) of the world’s offshore turbine fleet, up from 39 percent in 2021. In Europe, where expansion progress has stalled, both the EU (26%) and the UK (19%) boasted significantly smaller shares, according to satellite data analysed by the German Aerospace Centre (DLR).

Beyond concerns about price competition linked to cheaper labour costs, state support, and less stringent regulation, security experts also warn against the risk of relying on foreign suppliers in strategic sectors such as energy infrastructure. In 2025, Germany's economy ministry and the European wind industry launched a "resilience roadmap" aimed at reducing dependence on Chinese permanent magnets and other turbine components. Despite these concerns, major energy companies oppose an outright ban on Chinese hardware, arguing that Germany’s planned expansion path cannot be achieved without access to global supply chains.